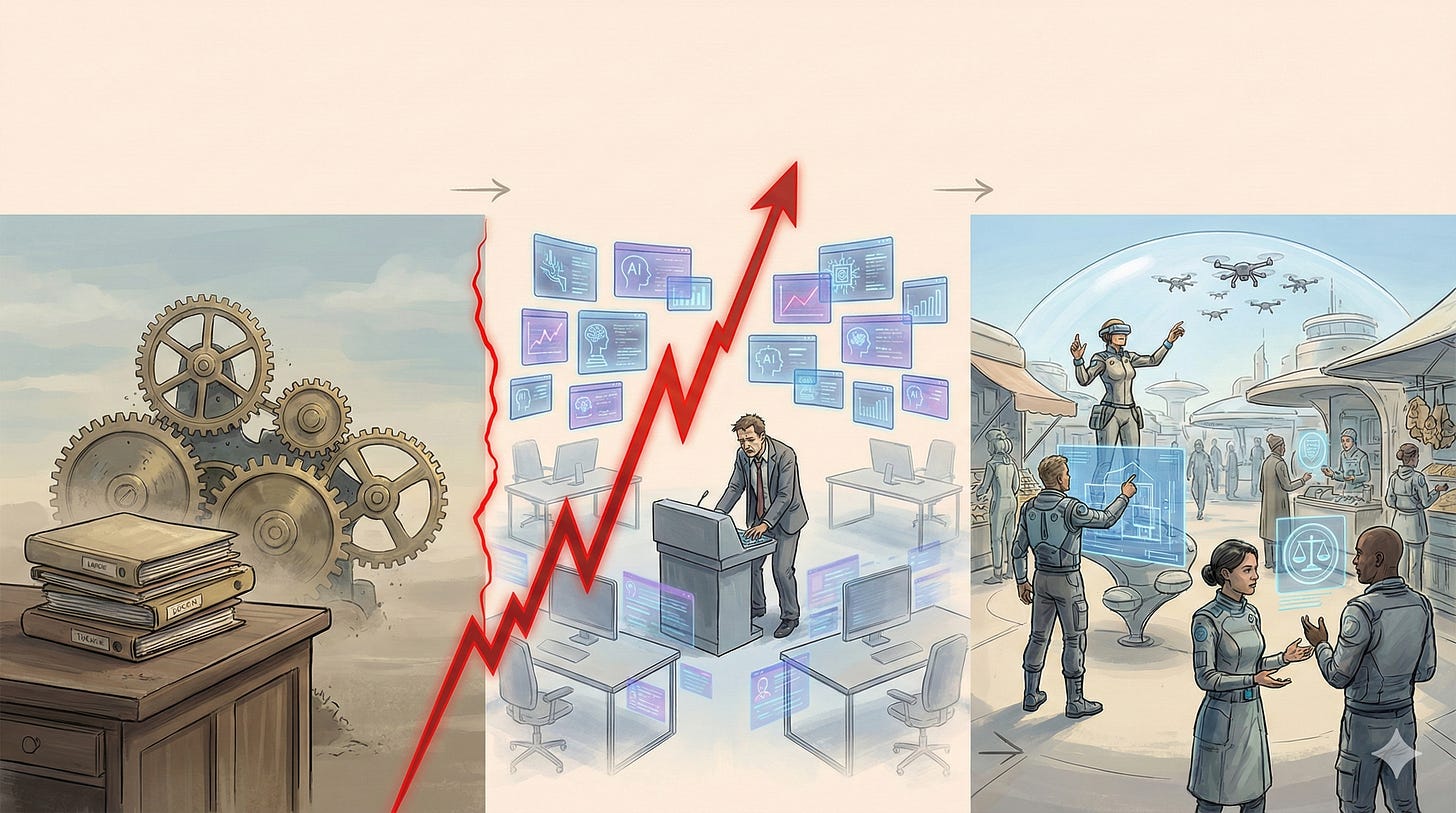

Will AI Take Our Jobs - Short term no, Long term, also no. Medium Term, hell yes!

Short answer:

Short term: not worried. because physics, and organisational inertia.

Long term: not worried either, because economic realities and faith in humanity.

Medium term: I am shit scared. We are ngmi.

Yes, this sounds inconsistent. So does everyone else’s AI take.

Right now the discourse is dominated by two kinds of LinkedIn philosophers:

AI is a toy, calm down.AGI is next quarter, sell your furniture.

Both are lazy.

I am am Indian, currently living in the UK. So, congratulations to me, I get to be anxious in two currencies.

India has a massive services export engine (often cited around the $400B mark) that props up urban middle-class demand and local consumption loops (IBEF, Economic Times).

The UK is also a service-heavy economy; one UK government assessment puts services at 81% of output and specialized services near 85% of exports (GOV.UK assessment).

So if AI eats service work, this is not a small change for either place. This is the destiny.

Short term: calm down, physics still exists

The last few months have felt like hyper-acceleration.

A while ago the vibe was “slopocalypse“. Now the same crowd sounds like they have discovered vibranium: Andrej Karpathy describing a workflow phase shift and skill atrophy (Business Insider), Boris Cherny saying he no longer hand-codes (Fortune), Pete Steinberger talking about getting pulled into a vibe-coding rabbit hole (Business Insider).

Even commit-share estimates are no longer cute: one recent estimate puts Claude Code at about 4% of public GitHub commits, roughly up from the ~2% zone in prior low-single-digit tracking narratives (SemiAnalysis). Now it is real enough for CFO slides.

And yet, zoom out for two minutes.

In 2020, Sharif Shameem’s GPT-3 React-component demo made everyone go “oh damn, text can generate JSX” (Prototypr writeup). From that moment to now, it feels like yesterday. But it has been six whole years.

Why six years? Because software moves fast, reality has to scale walls of physics.

The strongest models today were literally trained on GPU generations and cluster scales that did not exist in 2020 (Deloitte).

They run in data centers that had to be financed, built, cooled, and connected to a strained grid (CSIS).

Power is now such a bottleneck that even shuttered nuclear capacity is being brought back for AI-era demand (e.g. Three Mile Island Unit 1 restart plan for Microsoft-linked demand) (AP).

Scaling from GPT-3 era toys to GPT-5.x era production agents is not just a model story. It is a semiconductors + grid + capex + regulation story. In other words: physics.

But that’s just the model. Physics is only half the drag. The other half is org charts.

We have already seen this movie once. It was called “digital transformation.”

That phrase became such an MBA meme that entire ecosystems were built around holding workshops about holding workshops.

And yet the underlying point was true: changing large organizations is painfully slow.

McKinsey’s transformation research found overall transformation success below

30%, and digital transformation success at just16%sustained success (McKinsey).In healthcare, moving from paper-ish workflows to EHR-heavy workflows took more than a decade at national scale; office-based physician EHR adoption went from

42%(2008) to88%(2021) (HealthIT.gov).Federal legacy modernization moves in geological time: GAO’s 2019 list of ten critical systems had only three completed by February 2025 (GAO).

Now look at enterprise gen-AI adoption and the pattern is familiar.

Workers are moving faster than institutions:

75%of people report using AI at work, but78%of AI users bring their own tools because company rollout/governance lags (Microsoft Work Trend Index 2024, Microsoft release).At the org level, scaling is still the bottleneck: McKinsey’s 2025 survey says nearly two-thirds are still not scaling AI enterprise-wide (McKinsey 2025).

Gartner found only

29%deployed GenAI (Q4 2023), with proving business value as the top barrier (Gartner).

And yes, before someone says “but adoption is exploding,” that is also true.

OpenAI says it crossed 1M business customers and 7M ChatGPT-for-Work seats (OpenAI, Nov 5 2025). Anthropic and partners are announcing giant rollouts like Cognizant’s 350,000-employee deployment (Anthropic).

So this is the correct short-term picture:

the coding crowd is sprinting,

vendors are scaling fast,

but legacy enterprises are still negotiating budget codes, risk committees, and compliance templates in triplicate.

Bill Gates’ old line still holds: we overestimate short-term change and underestimate long-term change (quote reference).

So yes, Twitter may feel like everyone is on Claude already.

But no, we still cannot fire all SDEs across the industry and replace them with infinite tokens this quarter.

Short term is still transformation, not instant replacement.

Long term: we will invent work, because capitalism needs customers

I am much less worried about the long term, and not because I am naive. Because I have seen humans.

Humans are unbelievably good at inventing activity, attaching status to that activity, building a market around it, and then calling it “career growth.”

Graeber called out the phenomenon years ago in Bullshit Jobs (Simon & Schuster). His framing was moral critique. I am making a colder macro argument: some of this “made-up work” is what keeps demand alive.

History already shows the pattern.

In rich countries today, agriculture is tiny in employment terms: often just a few percent; OWID summarizes this shift across centuries (OWID insight).

For a concrete modern anchor, OECD puts US agriculture at around

1.4%of employment in 2023 (OECD).Global employment shifted massively from farms to services: services rose from

34%to51%(1991 -> 2019), agriculture fell from44%to27%, industry sat around22%(OWID, ILO data).

So yes, maybe not literally 100. But effectively for a long time in ancient history, almost everybody’s day job was “help humans not starve.”

If you explained “SEO specialist”, “product manager”, “actuary”, “growth marketer”, or “developer relations engineer” to a medieval peasant, he would assume you were either joking or collecting taxes in a new way.

He would be wrong. We invented those jobs. We staffed those jobs. We made PowerPoints about those jobs.

And we will do it again.

Why? Because money has to move.

The equation of exchange is boring but brutal: MV = PY (money supply x velocity = nominal output). If V collapses, the machine chokes (ECB explainer, FRED velocity series). Rich people cannot spend for everyone else forever. If the mass market has no income, asset values become theatre.

We already saw a mini-version during the COVID shock: when spending froze, everything started seizing up fast (St. Louis Fed).

So yes, Dario Amodei can warn that entry-level white-collar disruption could be 50% in 1-5 years (Amodei essay, Axios interview coverage). That’s a serious medium-term warning, and I take it seriously.

But Dario’s default answer often sounds like “fine, then we redistribute and people retire early.” That’s what a brilliant lab founder says when he models systems. The real world is messier: people don’t just want income, they want role, status, routine, identity, and something to complain about on Monday morning.

Long term, “everyone unemployed forever” is not an economic destination. It is an economic segfault.

If machines did all useful work, humans would still invent new paid complexities and curiosities because that is what keeps society stable and markets alive. We literally built massive industries around non-essential fun: games alone support 350,000+ jobs in the US (ESA) and around 73,000 in the UK ecosystem (Ukie).

So my long-term bet is boringly human:

We automate old work.

We panic.

We invent new “real” work, plus some premium nonsense work.

We call it progress and pretend this was always the plan.

Medium term: this is the part that scares the hell out of me

So we are clear that ...

< 5years: mostly safe-ish, because transformation is slower than Twitter.> 20years: probably safe-ish again, because humans rewire economies to keep money and meaning flowing (and yes, lower fertility means fewer net entrants in many countries, which eases some labor-pressure math at the margin) (OECD fertility trend, UN DESA fertility brief).

So what about the ugly middle: 5-20 years?

That part is terrifying.

Not because of a sci-fi “fully autonomous corporation” overnight.

Because leverage changes faster than institutions.

One senior who used to run 10 juniors can now instead supervise a farm of 20 AI agents running in parallel.

And this is no longer theory theatre:

Anthropic’s own engineering post documents

16parallel agents building a Rust-based C compiler across nearly2,000sessions (Anthropic engineering, Feb 5, 2026).Anthropic’s Opus 4.6 page explicitly positions the model for coding, agentic workflows, docs/spreadsheets/presentations, and financial analysis in enterprise contexts (Anthropic Opus 4.6).

On legal reasoning specifically, Anthropic cites

90.2%on BigLaw Bench in customer testing (Anthropic Opus 4.6).

So medium-term risk is not “autopilot plus legal signoff.”

It is managerial span explosion.

One experienced human + many machine workers = fewer entry seats for humans.

India: when the seat-selling model gets kneecapped

India’s IT-BPM sector is huge (often quoted around $250B+ and 5M+ jobs) (IBEF).

India’s broader services exports are now near $400B ($387.5B in FY25 by official reporting) (Ministry/PIB release via Commerce, IBEF summary).

That sector historically monetized headcount. AI monetizes outcomes.

And we should be honest about the baseline quality problem in entry funnels.

Mercer | Mettl’s 2025 graduate index puts overall employability at

42.6%, with technical-role employability at42.0%and non-technical at43.5%(down from48.3%in 2023) (Mercer | Mettl PDF, Mercer summary).In BPM specifically, a NASSCOM-Indeed report (as cited by ET) says nearly four in five organizations see a widening demand-supply skills gap, and

47%cite lack of adequately skilled candidates as a top challenge (Economic Times report on NASSCOM-Indeed study).

A lot of enterprise math now starts with some version of this uncomfortable ratio: junior knowledge-worker salary vs agent-seat cost.

Now combine that with rapidly improving agentic capability (including multi-agent compiler builds and high legal benchmark scores in production narratives) (Anthropic engineering, Anthropic Opus 4.6).

The first jobs to get economically nuked are obvious: the “convert specs into code/process/output” layer.

Those roles are not morally worthless. They are just increasingly one-shottable.

If your core job is turning a ticket into predictable output, you are already competing with an agent farm; the redundancy is real, the news is just delayed.

If clients stop paying for seats and start paying for output, everything changes:

junior hiring gets cut,

margins get squeezed,

top AI-native talent captures outsized upside,

and the urban consumption flywheel takes second/third-order hits.

And that second/third-order part is the real fear.

Private consumption in India is roughly 61.4% of nominal GDP in FY25, with PFCE growth 7.2% (DEA Monthly Economic Review, May 2025).

If a large chunk of urban salaried demand gets hit, this is not just an IT payroll problem. This spills into restaurants, food delivery, entertainment, rentals, mobility, retail, and the entire ecosystem selling to the urban earning class.

Losing momentum in a near-$400B services-export engine is not a rounding error.

Can India adapt? Obviously yes.

Will that adaptation be socially painless? Obviously no.

UK: high-value services are still services

The UK story is not “factory robots.” It’s “time-sheet economics under algorithmic pressure.”

Official trade stats show where the exposure sits: UK services exports are led by “other business services” and financial services; “other business services” explicitly includes legal, accounting, and management consulting (UK Trade in Numbers).

This matters because billable hours are the revenue plumbing of large chunks of UK professional services.

And that plumbing is under pressure:

Thomson Reuters’ UK legal market report says hourly billing still dominates (

62%), but clients are pushing hard on value pricing (State of UK Legal Market 2025 PDF).In the same report,

64%of corporate legal teams and58%of law firms expect a smaller share of hourly billing within five years (same report).

Inference from those sources: if legal pricing logic is shifting from time-input to value-output under AI pressure, accounting and consulting (which share similar time-based commercial DNA in many engagements) are unlikely to remain untouched.

Different unit economics from India. Same structural direction.

The part nobody wants to say out loud

The medium-term threat is not “no jobs”.

It’s “no ladder”.

If juniors are too expensive relative to AI, companies hire fewer juniors.

If fewer juniors are hired, the senior pipeline hollows out.

If the pipeline hollows out, the system becomes brittle.

Everyone says “be an AI orchestrator” like that’s a Hogwarts house assignment.

Nobody explains where that judgment is supposed to come from if apprenticeship disappears.

This is why the medium term is terrifying.

Not because humans become useless.

Because institutions become shortsighted.

My actual stance

Short term: don’t panic. Learn faster.

Medium term: panic a little. Learn much faster.

Long term: trust adaptation, but don’t romanticize the transition.

If you’re in India, don’t assume the outsourcing-era ladder will save you.

If you’re in the UK, don’t assume professional services are naturally AI-proof.

If you’re anywhere, assume your current job description is a temporary document.

“AI will create new jobs” is probably true eventually.

“You personally will be fine during the transition” is not a claim any honest person should make.

When ML algos started becoming good, it was thought boring repetitive tasks would be automated first. in reality, opposite happened. it was creative jobs like designing, coding, writing that AI excelled at. so hard to predict what trajectory this'll take as it evolves.

Whoever gets hands on first AGI will have massive advantage over others and probably no competition imho.

That's a much pragmatic take, considering the second order effects of it, great read ! definitely gave a new perspective : )