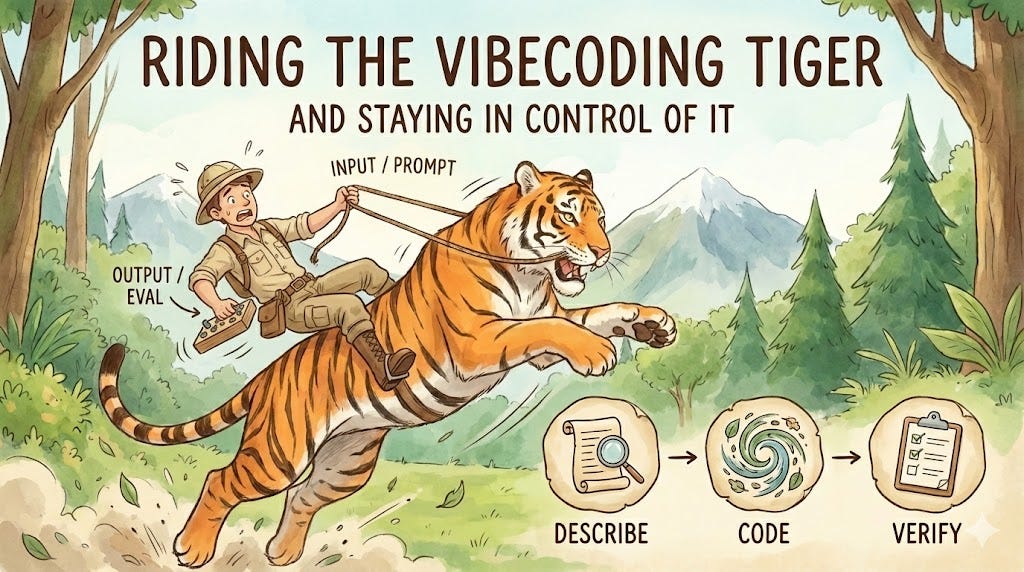

Riding the vibecoding tiger and staying in control of it

How to keep using agentic engineering for larger codebases without spiralling out of control

The paradox of agentic engineering is all about not letting the code sprawl outside the bounds of what you can recover from. It is not very different from onboarding a bunch of engineers to your team as a technical founder, because you don’t have time for everything. It is all about figuring out exactly how to make sure you are still at the steering wheel of the entire thing, but still effectively delegating work to everyone.

The 3 Steps

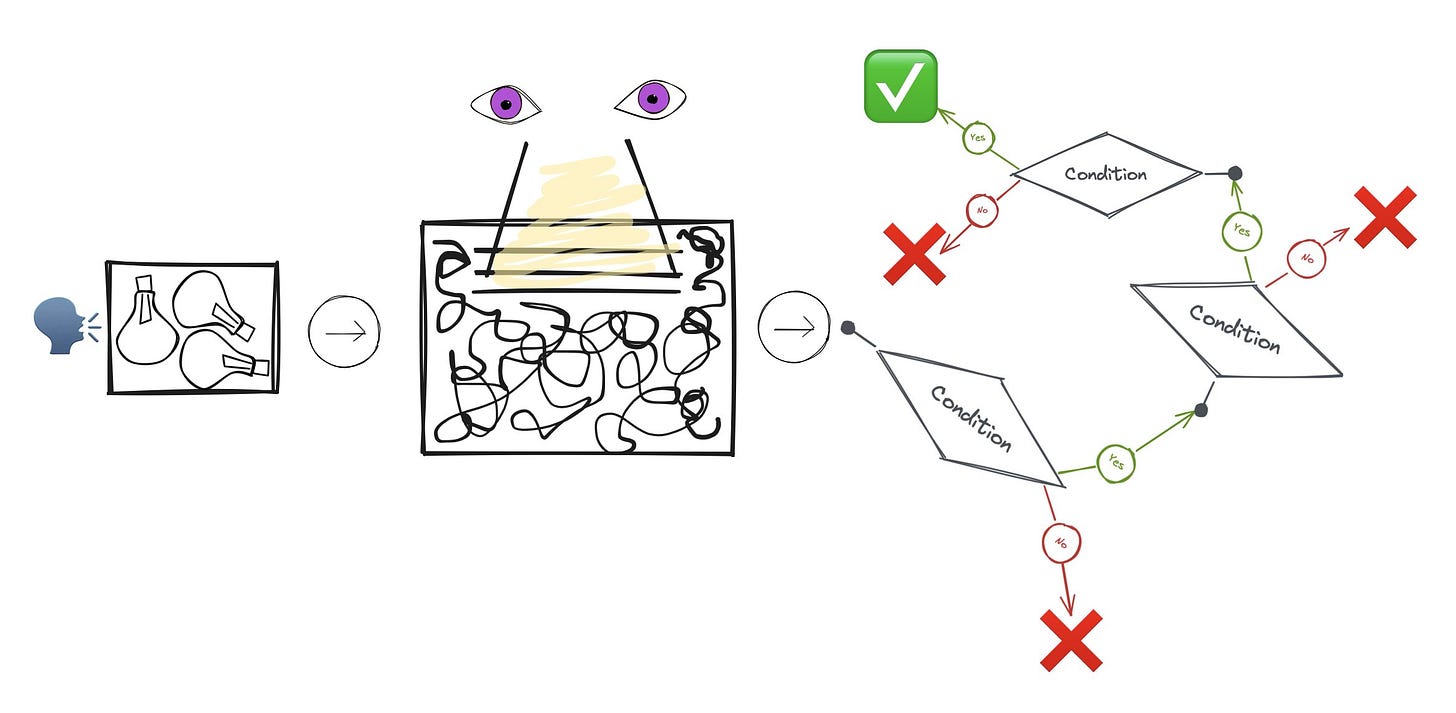

When you think of building software, or adding one feature to an existing piece of software, there are 3 stages of the process.

Being able to describe what you want. In a startup, often you can just “verbalise” it, and in terms of agents your prompts are this. Your ability to exert “control” over where the software is going starts from here. The more you can describe exactly what you want, the closer to that reality you’ll get things. In fact some of the best outcomes I have got from both getting work done from junior engineers as well from Claude as been when ‘what’ I wanted to be built, I could completely visualise in my head. When I very clearly knew exactly how it would work and look and function even before it was built, it was always easier to get it built. I would imagine some of the most brilliant movie directors can see the movie in their head even before they make it.

Observing the code itself. Whether it is peering over the shoulder of a human software engineer while they code, or through the flickering CLI of Claude Code or Codex. Seeing the code appear - you start to make sense of how it is being implemented. Depending on how big the task is, and how complex the project already is, for smaller, simpler cases you can literally dry run in your head what is going to happen as each line of code appears. In your head you can see the variables moving from one register to another memory address, you can see the http port open and the bytes flow. And if you are 100% in control of this stage (as you are when you are writing the code yourself) you can stop the process in the middle if it is going in a direction vastly different from what you intended this thing to be.

Finally verifying that it does actually work the way you intended it to work. And this can either be extremely easy as ‘eyeballing’ it, or extremely tedious as testing the flow/process for every possible variant of data that will pass through this feature/pipe/function and making sure it does indeed respond to every input with the output that you want it to. Sure that’s all just an elaborate way to say the term ‘software testing’

Most of the process of building software (and getting software built) is doing these 3 steps over and over again.

Taking your eye off

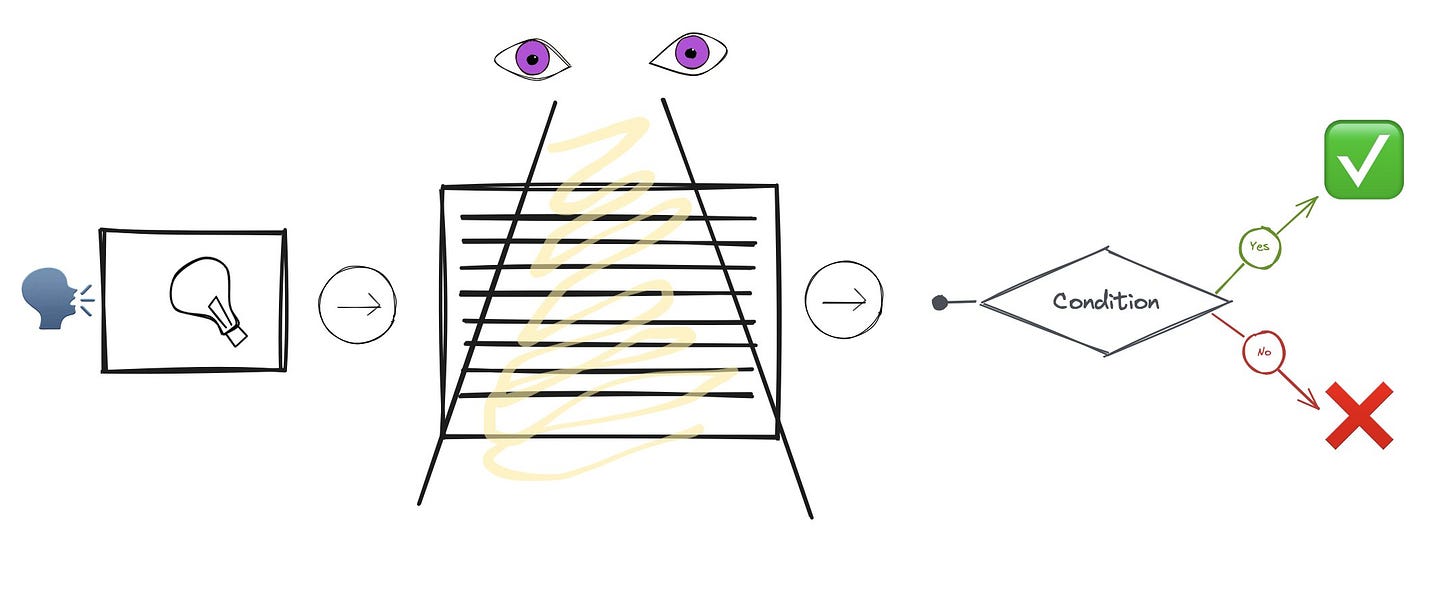

The spiritual process of delegating the work (assuming initially you were alone doing the whole thing), either to other humans, or to agents, is gradually taking your eye off the middle stage.

You want to be able to take your eyes off. You want to feel less anxiety as you stop reading all of the code, and just glance it once. You want to trust your instincts that if the description of what you wanted was detailed enough, and as long as you can trust yourself to be able to evaluate the output later, you can let go of reading every character as it appears on the screen.

Everyone who has gone from being the sole developer of a project to onboarding more engineers to it - especially hiring juniors and letting them ramp up, has gone through the process.

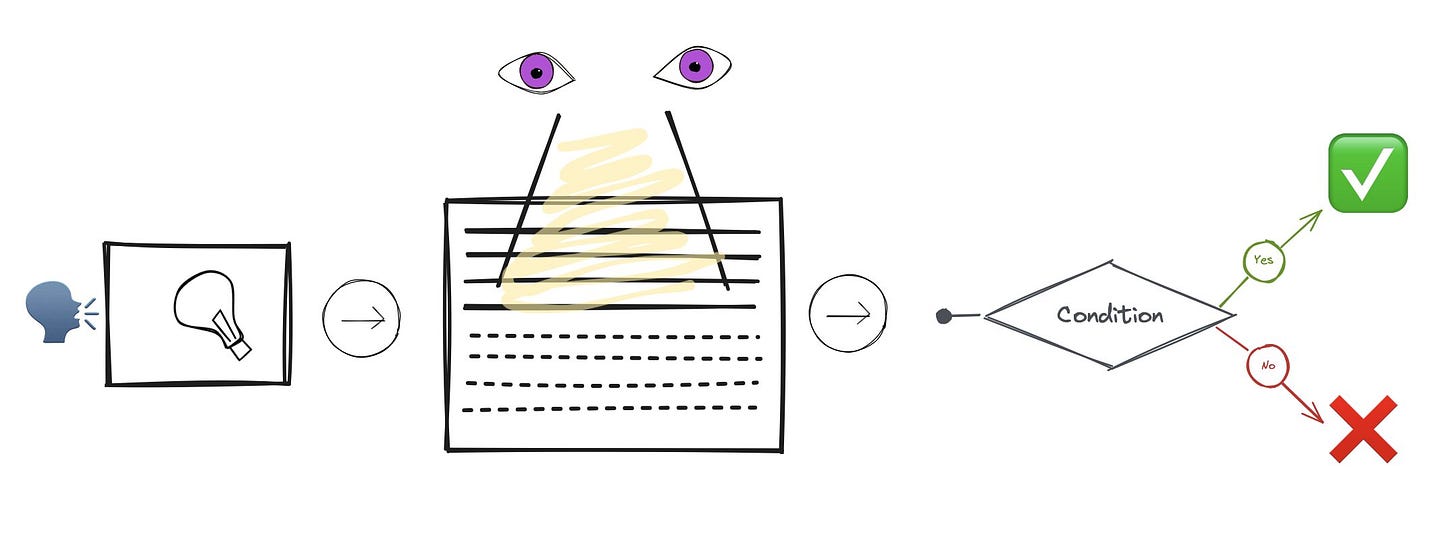

There is a lot to make peace with here

The code won’t exactly be what you would have written it had it been you at the wheel. That is fine. You are not at the wheel for a reason - you’re saving time to do other things only you can do

Even when you evaluate it to do exactly what you intended it to do, the code could still have been less than optimal, or simply just not the way you would have wanted it to be have been written. You need to let that be. It is important it does what it was supposed to, not necessarily look a certain way

The more it diverges from your vision of what the ideal codebase should have been, the less likely it is that you can fix it and rein it in if everything goes for a toss! Yes this is true, and this is the only part we need to talk about here.

Once you overcome the fear of delegation and the anxiety of “letting the agent rip”, you can truly free yourself up to think of many more ideas from the time saved from coding each one up. Anyone who has successfully levelled-up through delegating knows the journey.

Abstract, modularise, parallelise

The most important bit is calibrating your working style with agents to find the line in the sand on how much sprawl in the code is too much sprawl. How messy is too messy, and you need to pull back. How much of your nitpicky coding standards you can sacrifice, and at what point you need to pull hard stops at.

How to thread the proverbial needle?

Every day you let the agents write a bit more code that you wouldn’t trust it with earlier. Every day you keep your eyes off for a little bit longer. Every day you dip your toes a bit more into the waters of “parallel agents”. What if instead of one task, I give 5 agents 5 different tasks and then merge it all later? Tempting idea.

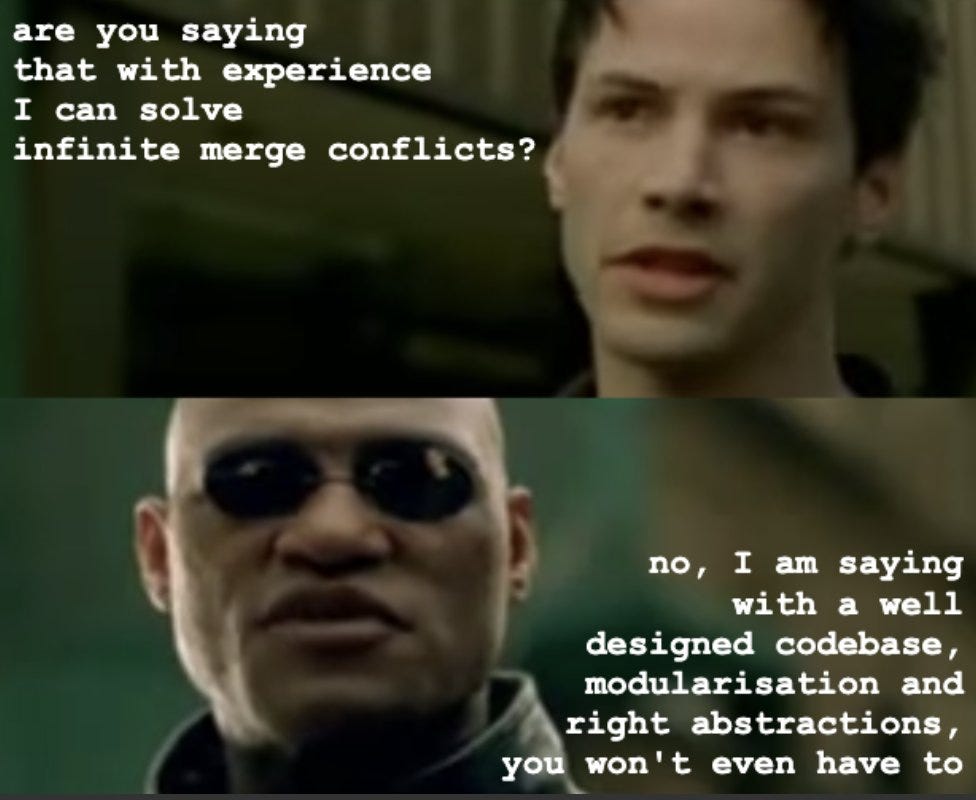

Delegating to humans is not a very different journey. Less experienced engineering managers and tech leads often say things like “don’t work on that part of the codebase, someone is working on things that will change it anyway”. As you master the art of orchestrating multiple people wandering around you codebase, you learn to modularise, create ‘contracts‘ between moving pieces, and make it easier for more and more people to simultaneously operate on the same parts of the codebase, and still keep the plates spinning.

Not letting it spin out of control

The hard part is not giving in to the lures of multiple parallel agents, and letting 10 of them make parallel changes to the codebase. The hard part is not in accelerating your output to 10x, 20x, 30x generating 100+ commits a day. The hard part is not riding the tiger 🐯. The hard part is to not fall off and also make it go where you want.

Every time the agent guesses something correctly that you didn’t specify in the prompt, you are tempted to be that little bit more ambiguous in your next one. Every time the agent writes yet another 5000 LoC commit, that is hard to read, but still passes all the tests, you are tempted to push it for an even bigger change. Every time the code review agent catches a mistake made by the coding agent, your are tempted to keep your eye on where the codebase is going a little less.

The hard part is learning exactly when did you and your army of agents truly cross the rubicon, the point of no return, the dark place where the agents are not doing what you want them to. Where you are unable to piece together the exact set of rules to test to evaluate you even are building what you want to build or not.

You now have fallen into a deep chasm between what you had started building from and what you wanted to build towards. A place from where you cannot “refactor” your way out of the unmaneuverability of the codebase. From where you cannot beat the immaleable codebase into shape any further. You kept your eyes off so long that you cannot start making your way into the impenetrable tangle of logic to untangle it anymore.

But you don’t reach this point completely unaware of it yourself. In fact, you feel the thrill of skating too close to the edge every time you merge some code that just felt off but it still worked. There is a hint of achievement every time you get soooo much more done than you ever thought was humanly possible, even though you are starting to see the seams giving away.

But you do have to fall into this hole once to even know it exists. To be able to retrospect and realise that the signs were there. It wasn’t that you were completely caught off guard, but that you knowingly let your guards down.

Drawing the line in the sand

How would you know the codebase is spinning out of your hand before the next time it happens? How do you know when to stop pushing the agents to more and more uncontrollable fission of the code?

While I don’t have very good answers (I am figuring out a lot myself), some of what I have figured, and from past experience of leading non-AI, actual software engineering teams are these

Reproducibility > Magic. If you ever start feeling that the agent is conjuring up magical things that you didn’t even specify in your prompts, you are already on the edge. The more you rely on the agent taking good assumptions to fill in the gaps of your requirements to create what you wanted, the less you are in control of the destiny of the codebase.

Every problem can’t be solved by writing more code. Many times you codebase needs to take a turn where it needs to shed some of the code. Sometimes you need to delete large parts of wrong direction you took. Often after wiring up a few complex flows, you discover commonalities and delete a lot of ‘WET’ code to make ‘DRY’ alternatives. Over the lifetime of a codebase, there must be changes that reduce the codebase too. If every change you are asking of the agents leads to them always writing more code (as they usually tend to), it again is a sign of a codebase sprawling out into something you won’t be able to tame later.

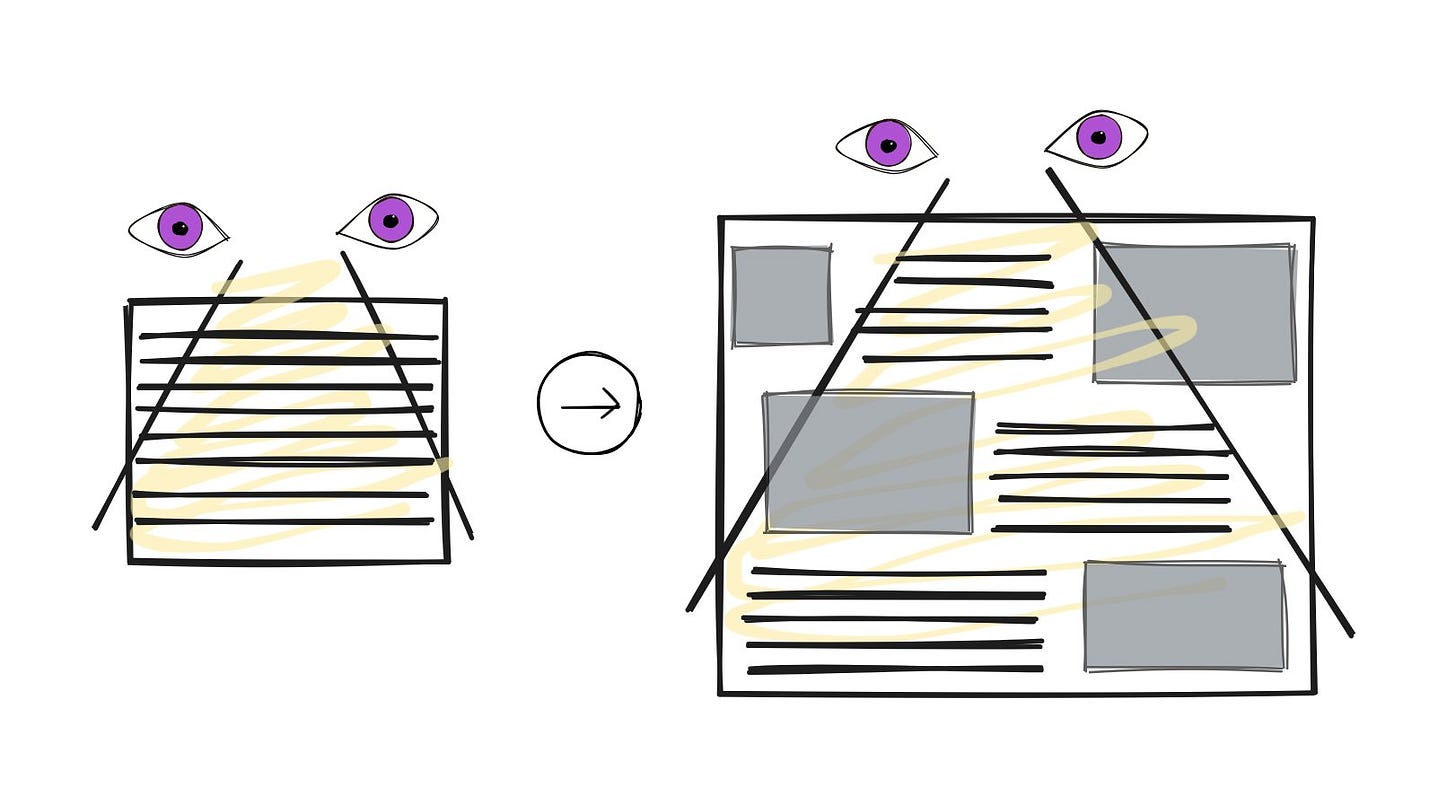

You can only control what you can verify. Tests/evals/verification whatever you call it - the loop is finally closed by them. Even outside of objective test coverage percentage numbers - the less and less surface area of the codebase you feel there are some eval that covers, the less control you have over verifying everything works. Unit tests and other verification tools for small bits of the codebase are less helpful. The more end-to-end evaluation mechanisms you have, less you can worry.

If you let the agents loose through the codebase gradually, at a pace at which you can continue to handle the cognitive load of the speed of its expansion, you can continue to build it biggger and bigger, more and more complex. There is no limit to how complex a system one can design, as long as they keep “blackboxing” the correct abstractions.

It is wrong to conclude that there is always a certain size of codebase beyond which things will get outside your control and you cannot keep an eye on what is going on. Projects like OpenClaw, and OpenCode are being actively built in public by people who clearly are writing code via agents primarily, and are fairly large in size - not the size you can always keep entirely floating in your head. But as long as you can create these blackboxes in the codebase that in itself is a durable, robustly tested, and encapsulates a non-flaky part of the logic, you start thinking of the system as a composition of these boxes, and you only need to actively keep an eye on lines of code of only the parts that are currently moving fast, or changing.

But if you don’t, and once you let the Flying Spaghetti Monster™ consume your codebase, it is hard to go back.